Some hae meat and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it,

But we hae meat and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankit.

Burns Night & Burns Suppers

From Celtic Canada -January 23, 2021

Have you been practicing your Selkirk Grace?

Burns Night is just around the corner and you certainly won’t be stuck for events and Burns Suppers around the world this Burns Night!

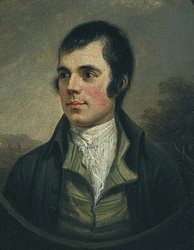

Celebrated annually on Robert Burns’ birthday, 25 January, Burns Night gathers Scots and Scots-at-heart around the world to pay tribute to the great poet’s life and works, and the holiday is marked by a jam-packed programme of festivities across the country.

Burns Supper place setting at Prestonfield House, Edinburgh

Burns Night! and Why Should it Be?

With shows and events for all tastes and ages, the ceremonies range from small, informal gatherings to large-scale dining experiences full of pomp and all sorts of entertainment, from an Interactive Haggis Hunt to light shows and more. But what they all have in common is that they centre around key Scottish traditions: there will be haggis eating, whisky toasts, poetry readings and songs, before everyone joins in the ceilidh dancing. And most importantly – good company and loads of fun!

Robert Burns from a Scotsman’s point of view:

This is the first time I have the tackled the Immortal Memory and in doing so, it begs me to ask the question – why do the Scots make such a fuss about Robert Burns?

Probably, you may think, he may be popular because he was a good poet. Perhaps. Maybe it is just another excuse for a right good bevvy? Fair enough, but we can do that anytime, but bear with me while I attempt to explain the adoration which surrounds this exalted man and his work.

Robert Burns was born on 25 January 1759 in the village of Alloway in Ayrshire.

A cultural icon in Scotland and among Scots who have relocated to other parts of the world, his birthday is celebrated almost as a second national day. For much of his life he was involved with the land and physical toil and knew well the difficulties of poverty and deprivation. Nevertheless, as a young man he had taken to writing poetry, much of it in his native Scots language. This was unusual at that time – as by the end of the 18th century, Scots was no longer regarded as the speech of the “educated”.

In 1786 Burns was preparing to emigrate to the West Indies when he published a collection of his poems in the town of Kilmarnock – “Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect”. The book (now known as the Kilmarnock Edition) was an instant success and instead of emigrating he went to Edinburgh where he was welcomed by a number of leading literary figures.

The money he earned firstly allowed him to travel. During his journeys he was to collect and edit many almost forgotten songs and, of course, obtain inspiration for further poetry. Despite the money which he earned from his poems, he still had to make a living in Dumfries. While trying to cultivate an unproductive farm AND carry out his duties as an Exciseman, he continued to write – mainly collections of songs which would otherwise have been lost forever.

Consider the time in which Burns existed, from a Scottish perspective. The son of a poor farmer, Burns was taught to earn a living by handling the plough. His father also saw to it that his son received an education that was worthy of any gentleman, including the study of Latin and French. For Burns, the future poet, it would open up an incredible new world.

The first books he read were a biography of Hannibal and the Life of Sir William Wallace which was lent to him by the local blacksmith. “The story of Wallace poured a Scottish prejudice in my veins which will boil there till the flood gates of life shut in eternal rest”, recalled Burns.

By the time he was sixteen, he had made his way through generous portions of Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, the works of noteable Scottish poet Allan Ramsay, Jeremy Taylor on Theology, Jethro Tull on Agriculture, Robert Boyle on Chemistry (of course we all know Boyle’s Law don’t we?), John Locke’s “Essay Concerning Human Understanding”, several volumes on Geography and History and Fenelons “Telemaque” in the original, that is, Burns read this work in the French in which it was first written in 1699.

His story illustrated how early reading and writing had become embedded in Scottish society, especially in rural areas. Despite the small population and relative poverty, Scottish culture had a built in bias towards reading, writing and education in general.

All this was down to the Schools Act of 1696, which was passed by the Scottish Parliament, and which ensured that every parish in the country had a school and a regular teacher. The Scottish view was that education was the right of everyone, not just the wealthy. As a result, Scotland became the first modern literate society in Europe and as the barriers of religious censorship came down, the outcome was a literary explosion.

It was mid to late 18th century, and Burns lived and worked during the time of the great Scottish Enlightenment. This was a period when Scotland produced more men of letters, more men of learning and more men of science than did any other nation on earth. For those of you who may consider this claim to be flirtatious or unfounded, it is well documented in the annals of world history, that in just about every discipline known to man, a Scot was at the forefront. David Hume was an eminent philosopher and one of the finest brains that Europe has ever known. His close friend was the eminent Scottish thinker Adam Smith whose book “The Wealth of Nations” turned the world of economics on its head when it was published, and formed the basis of modern economic philosophy. While these two were the pillars of Scottish intellectual achievement of the time, they were by no means the only heights. For Scotland had leaders in science, mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology, engineering, medicine, in jurisprudence and in exploration.

In architecture Scotland led the world with the Adam brothers from Kirkcaldy, who garnered commissions from St. Petersburg in Russia to Boston in the USA. Their influence spread throughout the world.

Yet notwithstanding all these great men of that time, it was the Star o’ Rabbie Burns that rose and shone above them all, and why should it be so? Why does that star shine more brightly than any other in the firmament of Scottish life and Scottish history? Perhaps, because of what Robert Burns did to preserve the literature, the language and the heritage of Scotland. Goodness only knows HE did more than any other. What is much more significant, he did it all at a time when a wave of anglicization was almost overwhelming his country.

You see, the interference of anglicization had begun as a trickle with the Union of the Crowns in 1603. It reached spring tide proportions with the Union of the Parliaments in 1707, but it became a tidal wave following the brutal crushing of the Jacobite Rebellion at Culloden in 1746 at the hands of the Hanoverian King George II.

Amongst such acts that the people of Scotland would find imposed upon them by a tyrannical institution, the bagpipe was declared an instrument of war and the tartan was banned, a proscription that would endure for 36 long and horrible years. Hundreds were executed; many more were transported to the colonies – a direct result of which by the way, is why we have places like Nova Scotia and almost 4.5 million Canadians of Scottish descent.

Robert Burns called them “evil days” and he wrote of them:

They banished him beyond the sea but ere the bud was on the tree

Adown my cheeks the pearls ran, embracing my John Highlandman,

but och! They catched him at the last and bound him in a dungeon fast,

My curse upon them every one, they’ve hanged my braw John Highlandman.

And all things English were being embraced.

Even the ladies of the night on the streets of the old town of Edinburgh, advertised their attractions, (however few), in the new English tongue, and schools teaching the newly arrived language were springing up all over the country.

That rising tide reached its high water mark in 1782 when to his eternal shame, the chief architect of the New Town of Edinburgh, created a perpetual memory to the very family who had presided over the greatest carnage ever known in Scotland, when he called the streets of his new town after them, and that is why we have George Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and the rest.

This wave of anglicization did almost irreparable harm not just to the language, but also to the culture and the heritage of Scotland. James Beattie, a Scots Poet of the day and a professor of Moral Theology in Aberdeen wrote, “Poetry is not poetry unless it is written in English.”

That, then, was the age in which Burns lived and wrote and that was the society in which his works appeared. Thankfully Robert Burns did not think the way of the likes of James Beattie and his ilk. When his works were published in 1787 as the Edinburgh Edition, he wrote the following letter to The Noblemen and Gentlemen of the Caledonian Hunt:

My Lords and Gentlemen,

A Scottish Bard, proud of the name, and whose highest ambition is to sing in his Country’s service, where shall he so properly look for patronage as to the illustrious names of his native Land. . . .those who bear the honours and inherit the virtures of their Ancestors? The Poetic Genius of my Country found me, as the prophetic bard Elijah did Elisha ….at the plough; and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and rural pleasures of my native soil, in my native tongue; I tuned my wild, artless notes, as she inspired.. . . She whispered me to come to this ancient Metropolis of Caledonia, and lay my Song under your honoured protection: I now obey her dictates. Though much indebted to your goodness, I do not approach you, my Lords and Gentlemen, in the usual style of dedication, to thank you for past favours; that path is so hackneyed by prostituted learning, that honest rusticity is ashamed of it. Nor do I present this Address with the venal soul of a servile Author looking for a continuation of those favours: I was bred to the Plough, and am independent. I come to claim the common Scottish name with you, my illustrious Countrymen; and to tell the world that I glory in the title. I come to congratulate my country, that the blood of her ancient heroes still runs uncontaminated; and that from your courage, knowledge, and public spirit, she may expect protection, wealth, and liberty. In the last place, I come to proffer my warmest wishes to the Great Fountain of Honour, the Monarch of the Universe, for your welfare and happiness. When you go forth to awaken the Echoes, in the ancient and favourite amusement of your forefathers, may Pleasure ever be of your party; and may Social Joy await your return. When harassed in courts or camps with the jostlings of bad men and bad measures, may the honest consciousness of injured worth attend your return to your native Seats; and may Domestic Happiness, with a smiling welcome, meet you at your gates! May corruption shrink at your kindling indignant glance, and may tyranny in the Ruler, and licentiousness in the People, equally find you an inexorable foe!

I have the honour to be,

With the sincerest gratitude, and highest respect,

My Lords and Gentlemen,

Your most devoted humble servant,

Robert Burns

Edinburgh, April 4, 1787

And so Burns wrote most of his poetry in Lowland Scots or Lallans as it was more popularly known, and in obedience to that aforementioned poetic genius.

At various times in his career, he wrote in English, and in these pieces, his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt. He wrote against the cultural tide running at the time and he wrote in the teeth of prejudice against his native language, but, he wrote with a beauty, with a simplicity that no other, whether before or after him, has ever achieved.

The greatest tale in any language is Tam o’ Shanter, just as the greatest satire is Holy Wullie’s Prayer, which is a condemnation of religious hypocrisy and self righteousness.

O Lord, Thou kens what zeal I bear, when drinkers drink, an’ swearers swear,

An’ singing here, an’ dancin there,

Wi’ great and sma’;

For I am keepit by Thy fear

Free frae them a’.

But yet, O Lord! confess I must, At times I’m fash’d wi’ fleshly lust:

An’ sometimes, too, in worldly trust,

Vile self gets in;

But Thou remembers we are dust,

Defil’d wi’ sin.

O Lord! yestreen, Thou kens, wi’ Meg – Thy pardon I sincerely beg;

O may’t ne’er be a livin’ plague

To my dishonour,

An’ I’ll never lift a lawless leg

Again upon her.

But, Lord, remember me an’ mine

Wi’ mercies temporal and divine,

That I for grace an’ gear may shine,

Excell’d by nane,

And a’ the glory shall be Thine,

Amen, Amen!

Burns also wrote some of the world’s greatest love songs, and while many others spend time on his notorious womanizing and his propensity to father illegitimate children, just as many ignore why his love for the fairer sex was sealed in immortality.

Till a’ the seas gang dry my dear and the rocks melt wi’ the sun

And I will luve thee still my dear while the sands o’ life shall run.

Thirty words ladies and gentlemen. Thirty, simple unforgettable words, and everyone a monosyllable. No one else could write with such simplicity.

Green grow the rashes, O;

Green grow the rashes, O;

The sweetest hours that e’er I spend,

Are spent amang the lasses, O.

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae fareweel, alas, for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

All of these things perhaps explain the immortality of the memory of Robert Burns to the Scots. But for an occasion such as tonight – what of his universal appeal?

Why is he so relevant to peoples all over the world, in a way that no other writer is?

Robert Burns lived in a world of either opulence or oppression. By accident of birth all were born with privilege or in poverty. With privilege there was wealth and position. Without it, there was destitution and despair. And it was that world of privilege and position, poverty and injustice that Burns detested and constantly condemned.

The sentiments of change, drastic change in society, then being kindled in Europe, were sentiments which would drive the Americans on to Independence and the French to Revolution, they were still an abhorrence to huge swathes of the privileged in Scotland and elsewhere. Burns, however, was above all, a humanitarian, one who cared for the people like no one before him. His sympathies were with the poor and the oppressed, the common folk, his fellow man. He had a love for all men that no other writer, before him or after, of any age, or of any country, had ever shown.

And so the pen of Robert Burns became the voice of the people; and he expressed the thoughts and their hopes.

He wrote –

“God knows I am no saint. I have a whole host of follies and sins to answer for. But if I could, and I believe that I do it as far as I can, I would wipe all tears from all eyes. Whatever mitigates the woes or increases the happiness of others, THIS is my criterion of goodness; but whatever injures society at large or any individual in it, then this is my measure of iniquity.”

No figure in world literature had ever written with such compassion for his fellow man.

Robert Burns left a message – a message for all men; for all nations and for all times. It is a message of friendship; a message of fellowship; but above all else a message of love. It is a message that is just as relevant and just as vibrant today as when it was written over two hundred years ago.

Then let us pray that come it may

(As come it will for a’ that,)

That Sense and Worth, o’er a’ the earth,

Shall bear the gree, an’ a’ that.

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

It’s coming yet for a’ that,

That Man to Man, the world o’er,

Shall brithers be for a’ that.

These are dynamic words, with a message so powerful, that they were spoken by former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan on the 13th January 2004, when he addressed the United Nations in New York.

It was the ability of Burns to depict with loving accuracy, the life of his fellow rural Scots. His use of dialect brought a stimulating, much-needed freshness and raciness into English language poetry, but Burns’ greatness extends beyond the limits of dialect. His poems are written about Scots, but, they are in tune with the rising humanitarianism of his day, and they apply to a multitude of universal problems.

Robert Burns is celebrated throughout the world, not only in Scotland, and we should wonder at why his life is considered so important. As Scots, we have had other poets, other writers, and other heroes, yet we do not afford them the veneration that we give to Robert Burns, whose works are translated into more languages than any other poet. Only 12 years ago 100,000 copies of his works were translated into Chinese, and they sold out within the week.

Why?

Perhaps more importantly why should other nations and other peoples celebrate the birth of a Scottish poet and why are these celebrations so unique?

For example the Irish have Joyce, the English have Shakespeare and the Americans have Longfellow. Every one of them an internationally known and respected figure, but none of them is paid the homage that is paid to Burns, (even in their own country never mind abroad).

There is no international acclaim of any of these writers, great though they may be.

Yet Burns is universally acclaimed.

When Burns died in 1796, the first celebration of his birth took place five years later in January of 1801, and from that moment forward, the institution of the Burns Supper has existed, and a chain of universal friendship and fellowship encircles the world because of it.

Wherever friends meet and friends eat, the name of Robert Burns is revered. When the Burns Supper in Auckland, New Zealand is finishing, it is still under way in Perth in Australia. Meanwhile they are sitting down in Kuala Lumpur and in Singapore. An hour or two later they are seated in Delhi. This chain of friendship follows the setting sun westward, through Asia, Russia, the Middle East, Africa, across the Mediterranean to Europe, to Scotland, even to Ireland and then over the Atlantic to Canada, across the continent of North America to its western seaboard and beyond. And so on, around the world and around the clock. On 25th January each year and for many days before it and after it, there is not an hour in the day or the night, when a Burns Supper is not taking place somewhere on this planet. In fact, there are Burns Suppers in over 200 countries in the world, and there is no other institution of man of which that can be said.

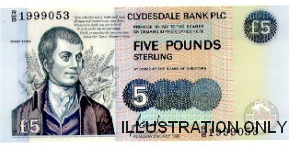

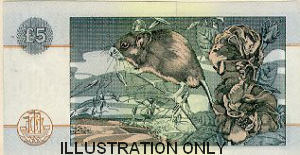

There are more statues of Robert Burns than of any other figure in world literature. Indeed, if we discount figures of religion, then worldwide, only Christopher Columbus has more statues than Robert Burns. No other writer of any nationality has been afforded such universal acceptance. His face has twice been commemorated by the Royal Mail, and since 1971, has been pictured on the £5 banknote of the Clydesdale Bank in Scotland. On the reverse of the note there is a vignette of a field mouse and a wild rose which refers to Burns’ poem “Ode to a mouse”. It is interesting that prominent historical figures depicted on other banknotes include Adam Smith and Robert the Bruce, and this is the high esteem in which Burns is held by his countrymen.

Why? It cannot be just for his poetry. For every country can boast of its poets. Scotland has produced other poets of the highest quality. Nor can it be on account of his prose, because Scotland produced two of the world’s greatest ever prose writers in Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson. Neither is revered to the extent of Robert Burns.

I would suggest that while we recognize the significance of January 25th, few among us, if any, would know the dates of birth of the aforementioned hierarchy of Scottish literature.

Robert Burns died at the age of only 37. We can but marvel at what he achieved and wonder what he might have achieved had he lived his full entitlement of three score years and ten.

On the day of his death on the twenty-first of July 1796, the funeral procession was wending its way through the crowded streets of Dumfries. Just as it arrived at the gates of St Michael’s Kirkyard, an auld buddy was heard to enquire “An wha will be oor poet noo?” A question which remains unanswered two hundred and eleven years later.

When William Wordsworth, perhaps the greatest of England’s poets, learnt of the death of Robert Burns, he wrote:

I mourned with thousands, but as one

More deeply grieved, for he was gone.

Whose light I hailed when first it shone and showed my youth

How verse may build a princely throne on humble truth.

Robert Burns and his memory will be immortal, not just to Scots peoples everywhere, but to people of every nation and every race and colour, whose lives have been touched by this unique genius.

Tell your children – aye – and your children’s children about him, and tell them just how lovely is the legacy which he left behind, for they will never have one that is more beautiful.

This, ladies & gentlemen, is my interpretation of the Immortal Memory.

If ever you are asked, as I have been, “why do we make a fuss about Robert Burns”, you will be able to answer.

Tell them that Burns did more to preserve the language, the culture, the heritage, the traditions, aye the very nationhood of Scotland than did any other. And he did it all when Scotland as a nation, faced the greatest threat to its very existence that it has ever known.

We Scots have a culture, a tradition and a heritage of which we should be immeasurably proud. For these are precious possessions that are equalled by few, and surpassed by none, and we owe more of that to Robert Burns than to any other individual.

I give you this toast, the proudest toast for any Scot to propose. It is also the proudest toast for any Scot to drink. For it recalls surely the greatest Scot of all time. It is a toast which we should drink with joy and with pride. Joy at his memory and pride in the heritage which he left us.

Ladies and gentlemen, fill your glasses – aye fill them to the very brim and raise them high, as I give you the greatest Scottish toast of them all,

“The Immortal Memory of Robert Burns”

Image source: Getty Images.

Image source: Getty Images.